- Home

- Margi McAllister

Archie's War Page 2

Archie's War Read online

Page 2

“Wish I could go,” said Will. “If I were old enough wild horses wouldn’t stop me.”

“Don’t be so daft,” said Archie. “You might get killed.”

Will shrugged. “I can take care of myself. Soldiering’s a real job. Fighting to save your country. That’s a real man’s job.”

“So’s gardening,” argued Archie. He admired the way Dad could shape a tree and bring crops from bare earth.

“Do you see Master Ted gardening?” demanded Will. “In the best families like our Carrs, the lads always do soldiering. They learn it at those posh schools they go to.”

“Yes, but they’re officers,” said Archie. “They’re in charge, they ride horses and have people to look after their kit and everything. You’d be an ordinary soldier.”

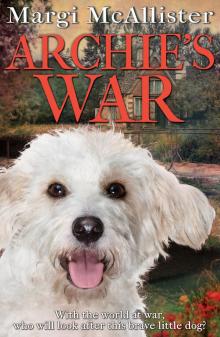

“So?” said Will, and pushed his empty glass towards Archie by way of telling him to take it back to the table. Master Ted was chatting to one of Dad’s assistants and looking so tall and lordly in his uniform that Archie had to stop and gaze – not for long, though, as Star made a dash for the front door and nearly knocked over a table on the way. Archie dived for him, picked him up, and headed for Master Ted. Star’s tail wagged ecstatically.

“Thanks, Archie!” said Master Ted as Star reached up to lick him. “Star, I need you to look after Mother while I’m away.”

Look after Mother? thought Archie. That thing couldn’t look after itself. Lady Hazelgrove had Connel. All Star would do was get under her feet and Connel’s big paws.

“Good luck sir,” said Archie awkwardly, and added, “we’ll miss you.”

“Thank you, Archie, but I won’t be away for long,” said Master Ted cheerfully. “I’ll be back for Christmas and making a nuisance of myself.”

He held out his hand for Archie to shake. Archie took it and felt strong and tall with pride.

“Good man,” said Master Ted. “Keep an eye on things here, won’t you?” While Archie still felt six feet above the ground, Master Ted carried Star to Lady Hazelgrove.

“Star,” he was saying, “you look after Her Ladyship while I’m – look at me when I’m talking to you, never mind sniffing for biscuits. Keep her out of mischief. And no fighting.”

He raised his head and spoke over the crowd to Dad. “And that goes for you too, Sparrow, if you were thinking of joining. Gardeners don’t start wars, and you don’t have to fight one. It should soon be over. One big punch up, and all over by Christmas.”

Before Dad was head gardener at Ashlings Hall, it had been Granddad. He was dead now and Dad had taken his place, but it hadn’t been that simple. Bertenshaw was older and thought he should be head gardener. He was a big man with a lump of a head and bristles on his face and arms. He scowled all the time and never spoke to any of Archie’s family if he could help it. He even scowled at baby Flora.

“Walter Sparrow only got that job because of his father,” grumbled Bertenshaw. But everyone on the estate knew that Bertenshaw was lazy and only did as much work as he really must. Archie’s Dad loved the gardens almost as much as he loved his own family. He didn’t make a fuss about it. Watching the neat, precise way he pruned a rose bush or pressed seedlings into the earth was like watching a musician. Dad wouldn’t let Bertenshaw prune roses. He was too careless, and too rough with them.

Dad had a way of teaching Will and Archie how to understand what the plants needed. “What’s it trying to tell you?” he would say if a tree was wilting or a bud failed to flower. When he’d been tiny, Archie had thought that the plants could talk and for some reason he couldn’t hear what they said. When he was older, he understood what Dad meant. Brown leaves or pinched buds were a tree’s way of telling you something was wrong. It was thirsty, or in the wrong place, or something was attacking its roots. All the other gardeners respected Dad and had no time for Bertenshaw. The morning after war was declared, Bertenshaw trudged past Gardener’s Cottage with a sneer, as if the war was all Dad’s fault.

Ma had grown up at Ashlings, too. Her father had farmed one of Lord Hazelgrove’s farms.

“Lady Hazelgrove still looks beautiful,” she was saying, the morning after war was declared. “I was watching her in the Great Hall yesterday, she’s as lovely as she was the day she was married, and more elegant now she’s older, and she walks like a queen.”

“I remember that wedding,” said Dad. “It was the biggest thing in the village for years. We all got a half-day holiday, and the children got sixpence. I were eleven year old, but I helped my Pa with the flowers. His Lordship wanted an arch of roses over the door and we did it, too. We were right proud of that.”

“At school we had to make a banner with their names on, Charles and Beatrice,” said Ma. “I designed a monogram and I thought it was beautiful, but I did it with C, B, and H, because I thought their surname was Hazelgrove. You would think so, wouldn’t you? I did this beautiful design and showed it to my teacher, and she said, ‘Don’t you know their name is Carr? Have you lived in this village all your life and you don’t know the name of the people at the Hall? His Lordship’s title is Lord Hazelgrove. His surname is Carr.’ And she went on and on about it, until I cried.”

“She was a nasty old broomstick,” said Dad. “I hated her.”

“I reckon she thought Lady Hazelgrove wasn’t good enough,” said Ma. “A lot of the women were like that.”

“Lady Hazelgrove not good enough!” repeated Archie.

“She wasn’t from one of the old families,” said Ma. “Her grandfather was an engineer who made whole mints full of money building railway engines. So the village said that she wasn’t a real lady, just a rich girl, but she looked and talked like a lady.”

“They all like her now,” said Archie.

“She spent her money wisely,” said Ma. “She got cottages repaired, she had water taps put in houses, she put up the money to pay the doctor’s bills for them that couldn’t afford them. And she made that horrible teacher retire, so the children all loved her. She was a sensible woman. She earned respect.”

“It’s the best way,” said Dad. “Respect should be earned. Now Archie, go and pick the peas and beans for the Hall and carry them up to the kitchen. And half a dozen lettuces, and find out if they want raspberries today.”

It was one of the jobs that had to be done every day, picking the fresh fruit and vegetables and carrying them to the Hall. Archie took a trug to the garden and picked the long green beans. War. It sounded exciting until you realized that people would really be shooting each other. Shooting at Master Ted. But Master Ted would come through anything. He had to, because life wouldn’t be the same without him.

In a cloud of white, Star careered through the garden. That dog was never where it was meant to be. He stopped suddenly at a row of cabbages and pushed his nose into the leaves.

“Star!” shouted Archie. The dog stopped and looked up, wagging his tail and looking hopeful.

“Where’s Ted?” called Archie, hoping that Star would look for his master instead of weeing on the cabbages. “Find Ted!” From a long way off came two short sharp whistles, and Star whirled round and dashed off towards the Hall. The kitchen garden was another place where gates were meant to be kept shut, but Star was small enough to wriggle underneath them. Couldn’t he be kept on a lead?

Archie lifted the trug, which was heavy now. He only went to the Hall to deliver fruit and vegetables to the kitchen, but he’d occasionally glimpsed the way the family lived. He didn’t envy all that ceremony. At Gardener’s Cottage they ate from earthenware plates on weekdays and Ma’s blue and white willow pattern on Sundays, and sat around a scrubbed wooden table with a cloth on it. He and Will shared a bed, and always had. Little Flora had a cot in Dad and Ma’s bedroom, but when she was bigger she’d sleep in the attic with Jenn. The bath hung up against the back wall of the house, to be put in front of the fire on bath nights. Ma thought their cottage was heaven. They ha

d taps in the house, and a stove that heated water. What more did they need?

At the Hall the family ate in a room bigger than their whole cottage, with silver on a table that shone like water. You wouldn’t dare spill anything. There was a room the size of the village school for sitting around in and another one just for a library, their own library. And everyone had their own bedroom along miles of corridors. Did they not get lost going to bed? Even Lord and Lady Hazelgrove had rooms of their own, and Ma said they had feather beds, too. Ma said that Lord and Lady Hazelgrove had little rooms for getting dressed in. Archie couldn’t understand why they needed them, but he was proud of the Carrs of Ashlings. They lived in style. The peas and beans in the silver dishes? The strawberries to eat with cream? We grew those. My Dad and Will and me, we grew those. And the best of the Carrs of Ashlings was Master Ted, who knew every child on the estate by name and had time to listen to everyone. Star might be more trouble than he was worth, but he knew a good master when he saw one.

Master Ted had always got on with everyone on the estate. He’d play cricket and footie with the village kids. He used to take Will and Archie fishing and he’d taught them to bowl overarm, too. Every year on Midsummer Day, the longest day of the year, he led the Hall team in the Hall versus Village Dawn to Dusk Cricket Match, which began at sunrise and ended at sunset. There was no limit to the numbers on the teams, so almost all the men and boys in the village took part and tea was served from a marquee on the lawn. That summer, Archie’s proudest moments had been when he batted on Master Ted’s team.

In winter Ted joined in with snowball fights and sledging. One bitter morning three years ago, when Archie had been carrying vegetables to the house, he’d slipped on the ice and hurt his foot so badly that he couldn’t walk, but Master Ted had seen him, scooped him up, and carried him back to the cottage where they’d all sat drinking tea at Ma’s table, Archie with his bandaged foot up on a chair. They’d eaten freshly baked lardy cakes, and Master Ted had licked the stickiness from his fingers and said it was much nicer than the cakes they got at the hall.

“There’s no side to Master Ted,” Ma had remarked later. “He gets on with anyone, and that’s the sign of a real gentleman.”

Now, from the back door of the Hall, Archie made his way to the Servants’ Hall, which smelt of soap and boiled cabbage. Aggie the big bony kitchenmaid was there and Archie gave her the basket.

“I suppose you’ll be off for a soldier, Archie Sparrow,” she said.

“He’s not old enough,” said the cook firmly. “And when he’s old enough, it’ll be over.”

“Hey up!” said Will next day, coming back from the village. “The army’s arrived!”

Archie looked over his shoulder, half expecting to see troopers in the kitchen doorway. Will laughed.

“Not here, you soft lummox. In village. In t’church hall.”

The soldiers had set up a long table in the church hall, he said, and senior soldiers – the recruiting sergeants – sat behind them. Any man old enough and fit enough to fight could sign up there.

“Oh, yes?” said Ma. “They’ll have a lad in a uniform before he can say, ‘Which way’s France?’”

“Sam Hardy tried to join,” Will told them.

“Sam the Boots?” said Archie. Sam was the boy who cleaned the boots and did other odd jobs at the Hall. He and Archie had known each other all their lives.

“Sam was standing up tall and swearing he was eighteen,” said Will. “But his Uncle David was in the queue to sign up too, and he told the officer the truth about how old Sam was, and then he got Sam’s granny, ’cause she lives across the road, and Granny Hardy barged in like storm and fury. She gave the sergeant an earful and dragged Sam back by his coat collar, marched him all the way back to the Hall.”

“How do you…” began Archie, but Will gave him a look that silenced him. Presently Ma left the room, and Archie felt it was safe now to ask the question.

“How do you know what went on at the recruiting office?”

“Everyone’s talking about it,” Will told him. “The first lot are marching off on Friday morning. I reckon Dad might let us go and watch. Give them a good send-off.”

“When’s Master Ted going?” asked Archie.

“Same time as the rest of them, eleven,” said Will. “He’s leading them off.”

Archie woke early and couldn’t get back to sleep so he pulled on his clothes, slipped quietly outside, and walked slowly and thoughtfully through the gardens. Gardeners don’t start wars. Master Ted had said that, and the words had repeated in Archie’s head as he lay in bed. Master Ted didn’t start wars either, but he had to go and fight in one.

In the autumn Dad had cut down an old cherry tree. It had been a grand old tree but it had withered and failed at last, and now the wood was stacked in the shelter of a wall. Archie and Will were allowed to help themselves to the small pieces and Archie, picking through them, found a short, thick piece of branch. He took it home and sat on the doorstep, paring at it with his penknife as the shavings curled to the ground.

He was fond of this penknife, which had been his present from the Carr family the previous Christmas. He was pretty certain that Master Ted had chosen it for him. Dad had showed him and Will how to carve simple animals and he’d intended to make a dog but the wood was all the wrong size and shape for a dog, so he sat scraping the blade steadily down the grain, waiting to see how it turned out. It seemed that even when a tree was cut down, it could tell you what it wanted. By the time he’d shaped it a bit more he thought it would make a good sword – a very small one, not much bigger than his hand, but still a sword – and turned it the other way to shape the hilt. He was still there when the smell of frying bacon wafted past him through the open door and made his stomach yearn with hunger. Dad came to the door and watched what Archie was doing.

“Nice piece of work, is that,” commented Dad.

“It’s for Master Ted,” said Archie. He’d only just thought of that, and realized he wanted to give Master Ted something he’d made himself. Until now it had just been a bit of wood to whittle, but now that it was a present for Master Ted it was precious. By breakfast time he had finished it, taking care with every stroke of the blade, and sandpapered it smooth. Finally, he turned it in his hands to inspect it. It needed a finishing touch.

“Has Master Ted got any middle names?” he asked.

“Your Ma would know,” said Dad.

“Francis Stephenson,” called Ma from the house. “Edward, then Francis, after his Uncle Francis, and Stephenson from Her Ladyship’s side.”

Everyone was in a good mood at breakfast time. The hens were laying well so there were plenty of eggs, and Flora soon had buttercup yellow streaks of yolk across her face. Jenn tried to clean it off but Flora didn’t want to be cleaned, and screwed up her face. She looked like a cross kitten.

“Dad,” said Archie, “may I go the village to see the men march off? They’re leaving at eleven from outside the church.”

“Me too?” asked Will with a mouthful of bacon.

“Manners, our Will!” said Ma sternly.

“Can I too?” pleaded Jenn. “I’ll take Flora, Ma, so she won’t be under your feet.”

“You can all go,” said Dad. “Give them a send-off.”

“Aye, if they must fight wars they may as well have something to smile about when they march away,” said Ma. “They won’t be smiling when they get to France, or Belgium, or wherever they get to.”

When Will and Archie put on their jackets to go to the village Ma was packing bundles into two willow baskets. Archie took the wooden sword from his pocket and began to carve “EFSC” into the hilt. Then he sandpapered it again, because it had to be perfect for Master Ted.

“There’s some Ashlings roses for the lads,” said Ma, her back turned to them as she bent over the baskets. “White roses for Yorkshire a

nd sweet pinks, and I’ve put paper and pins in there, too, they’ll need pins.”

“Ma!” exclaimed Will in horror. “Soldiers don’t want flowers!”

Ma whirled round with such a glare that they both stepped back and ducked. Her hands were on her hips.

“And what do you know, Master William Sparrow, all of fifteen years old, what do you know about what soldiers want?” She banged the basket on to the kitchen table so hard that petals drifted to the floor. “You don’t know you’re born! My cousins all fought in South Africa and I know a bit more about the world than you do.” Then she paused, and the fight seemed to go out of her. “I’ve known Master Ted since he were a littlie, and most of those lads, too. Off you go, now, and give them a cheer.”

It’s a good thing our Jenn’s going, thought Archie. She won’t mind carrying flowers.

The head gardener’s family weren’t the only ones walking to Ashlings village that morning. On the way they met with other families who worked for the Carrs, the carpenter and his daughters and the gamekeeper’s wife and children, and when they reached the church everything was as crowded and busy as a market day. A little crowd stood at the door of the Fox and Geese public house. Everybody seemed to have brought something for the soldiers, mostly photographs or little bags of sweets, so Archie was glad to have something to give even if it was flowers. He was even more glad to have the little wooden sword. Ever since that moment of understanding that it was for Master Ted, he had looked forward to putting it into his hand. Now, wherever Master Ted went, the sword would go too.

Archie looked round for Master Ted and couldn’t see him anywhere. A tall young lad stood still for his mother to tuck a prayer book into the top pocket of his tunic. A pretty girl slipped something into a soldier’s hand. Lord and Lady Hazelgrove stood beside the car where Star and the chauffeur still sat, and Archie guessed that they had already said goodbye to Master Ted privately. Lords and ladies didn’t do crying and hugs in public. The coalman was there, a couple of teachers from the grammar school in town, and Frank Roger who sang in the church choir. All the girls fancied Frank Roger.

Archie's War

Archie's War