- Home

- Margi McAllister

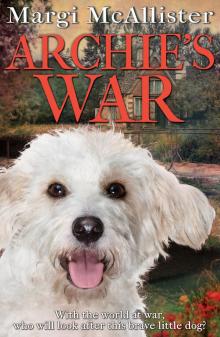

Archie's War

Archie's War Read online

For Edward and William Hall and in memory of their grandfather, Donald Crossley

Contents

Cover

Half Title Page

More by Margi McAllister

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Copyright

A rabbit ran into the walled garden and disappeared behind the apple tree. Archie ran to shut the gate but it was too late – a small dog, ears streaming behind him, was racing across the lawn after the rabbit.

Star was fast, and he loved chasing things. He darted under the bench then sprang over it, stopping for a second to sniff at a whiff of fox. But where was the rabbit? He veered round the apple tree and collided with it.

Star sat up. So did the rabbit. Alarmed, they stared at each other. Star shook his head because one of his ears had turned inside out, and sneezed. The rabbit came to its senses and ran.

Star had enjoyed the chase. He trotted back the way he had come, then stopped to inspect the stump of an old tree.

It was a great day for Star, who didn’t often get into the walled garden. There were windfall plums to play with, tree stumps, and so much to sniff – a wheelbarrow, a spade, a pile of branches. He loved exploring, he loved life, and with all his heart he loved his Master Ted.

He looked up and saw that somebody had come into the garden. It was the boy who worked here. Star thought about going to meet him, but he needed to leave his mark first.

Archie shut the gate behind him. Dogs weren’t supposed to be in this garden but somebody had left that gate open again and Master Ted’s useless little dog was having a wee on a tree stump. That dog must be four years old by now, but most dogs had learned a bit of sense by that point. Not this one. As far as Archie could tell it didn’t have half a brain from one end to the other.

“Star!” he called. “Come here, you daft thing!”

Star thought everyone was his friend so he ignored the smell of the compost heap and ran to Archie who picked him up, tucked him under one arm and set off towards the Hall. As Archie passed Gardener’s Cottage, his little sister Jenn, ten years old and big enough to be helpful, appeared at the door with baby Flora on her hip.

“Tell Ma I’m taking this thing back to the Hall,” he called to her. He could feel Star’s tough little tail wagging against him. Master Ted thought the world of Star, which was probably why the dog always expected something good to happen.

“I’m supposed to be helping my dad, not minding you,” Archie muttered. “Gardens don’t look after themselves.” True, there was a team of twelve gardeners, but Bertenshaw the under-gardener wasn’t much use to begin with and Archie was the head gardener’s son. He had to make a good impression. At least this way he might get a chance to see Master Ted.

The quickest way to Ashlings Hall led through the kitchen garden, across the west lawn, and past the rose gardens and flower borders that Archie’s dad was so proud of. Star wriggled to be down, but Archie held him more firmly so Star twisted round to lick his arm instead.

“Give over, nuisance,” said Archie. Star was as silly as a box of frogs, looked like a mop and wouldn’t know what to do with a rabbit if he landed on top of one. Most likely he’d hold up his paws and surrender. In the spring, when Dad had spread netting all over the vegetable garden to keep the birds off, Star had chased a cat across it. By the time they found him he was on his back and so wrapped up in netting that they’d had to cut him free with scissors. Always in the wrong place, always a nuisance. But the real trouble with Star was that he was no decent sort of dog for Master Ted. Master Ted was the son of a lord, and should have a proper grand dog.

“I said give over, you lummox,” said Archie, because Star was still licking him. The other dogs at Ashlings Hall were proper dogs for the family. Lord Hazelgrove was followed everywhere by Brier the retriever, golden and splendid as a lion, and Sherlock, the enormous black Labrador. Those were real dogs, man dogs, dogs for the ruling people. Lady Hazelgrove had Connel the deerhound, a tall shaggy wolf of a beast that walked by her side like a bodyguard, her head as high as Her Ladyship’s waist. A grand dog. But Star?

Nobody knew what Star’s father was, but as Star was mostly white and had a square sort of face, he was probably some sort of terrier. Master Ted thought there was a bit of Westie in him.

“Bit of spaniel, too, I reckon,” said Archie to the dog. “With that red-brown smudge on your head and your floppy ears. They’re like a pair of curtains, are those ears. You should be a lady’s dog.”

Ashlings Hall was home to the Carr family, but they weren’t just plain Mr and Mrs Carr. They were Lord and Lady Hazelgrove, and Archie was proud of them. The children of the Hall were all grown up now. There was Julia, the oldest and bossiest. She had married a rich Scottish lord, and now she was Lady Dunkeld. She and her husband had a Scottish castle and a house in Kent and spent most of their time there, which Archie couldn’t understand. Why live in a house when you had a castle, with red deer and wildcats around? Caroline, the second eldest, was married to a diplomat and travelled all over the world. They were in Norway now, Ma said. Then there was the first son, Simon, who was something to do with the navy but seemed to spend most of his time at a desk in London.

The youngest was Master Ted. The staff should really have called him Mr Ted now that he was grown up and an officer in the army, but everyone called him Master Ted, just as everyone loved him. He cared about people. He was good at sports, friendly to all the staff, and Archie’s hero. He knew every one of the families who worked for Ashlings Hall and it was Master Ted who had taught Archie and his brother to play cricket, and ride a bicycle. It was as if, when Ted appeared, you knew that very soon everyone would be having a grand time. Archie would have been happy to polish his boots. Master Ted should have had a tall faithful hound following him about, but all he wanted was a mongrel that looked like a scrubbing brush.

“No more sense than a scrubbing brush either,” Archie said to Star. “You needn’t think I’m going to put you down, you’ll only run off again.” Star was only there because somebody’s poodle got over the wall and had a litter of pups. Master Ted called him “Star” after the mark on top of his head. It looked more like a smudge to Archie. But there was this to be said for Star, he was devoted to Master Ted. Followed him like a shadow. You’d think that a proper gentleman like Master Ted would be embarrassed to be followed around by a soppy-looking dog like Star…

Archie’s freckled, wide-mouthed face opened into a grin of delight as Master Ted strode into sight. Archie put down the wriggling bundle of dog and Star galloped furiously to meet his master, wagging his tail so hard that he overbalanced, rolled, picked himself up, and hurled himself into Master Ted’s arms.

“Stop licking, you soft thing!” said Master Ted, but he was laughing, turning his head away from the pink tongue as he ruffled the dog’s ears. Star jumped down and darted about until he found a stone that Master Ted could throw for him, dropped it at Ted’s feet, and danced a few paces backwards. Ted bowled it like a cricket ball towards the trees and Star raced after it.

“I’ll get back to work then, Master Ted,” said Archie, but to his joy Master Ted didn’t just nod and tell him to run along. He looked down, and his kind dark eyes were smiling. Master Ted always seemed more alive than everybody else.

“Sorry about that, Archie,

” he said. “Has he done any damage this time?”

“No, Master Ted sir. I reckon he’s just been rabbiting. Didn’t catch any, sir.”

“He never does. Enjoying your school holiday?”

“Very much, sir!” He had to help Dad in the gardens all summer but he liked that better than school and there was still plenty of time for climbing trees, skimming stones on the lake, and kicking a ball about with Will, his older brother.

“Tell your father from me, the gardens are looking absolutely—” he was interrupted by the ringing of a bell so strident that Archie jumped.

“Telephone,” explained Master Ted. “Terrifying noise, scares the wits out of everybody. The gardens are looking absolutely splendid. Will you ask him…”

Archie didn’t hear what Master Ted said next. Mr Grant the butler was hurrying from the house, with such a grave look on his face that something must be wrong.

“Master Ted,” he said, “A telephone call from your brother, sir.”

Archie turned back to the cottage, and Star followed Master Ted into the house, carrying his new favourite stone. Archie had stopped to rub greenfly off the roses when Master Ted tore past him, running as if for his life, Star at his heels.

“Archie,” he shouted, turning to run backwards as he called, “I have to find my father! If you see him, if anyone sees him, he has to go back to the Hall! Immediately!” And he ran on. Archie gazed after him. Had somebody died?

When the morning’s work was done Archie sat down with Will for bread and cheese in the kitchen garden. Archie was thirteen and a half but Will was eighteen months older and no longer went to school. He worked side by side with Dad. There were rules between Will and Archie, the sort of rules that are never written down but everyone understands, and they all came down to the same thing – Will was the oldest. Will was the one who had the final say about pretty much everything. He was bigger and stronger than Archie, even allowing for age – Will was big-boned and solid, and Archie would always be skinny. Will had done more and knew more. Archie had to remember that. In return, Will guided and protected him. Will might occasionally thump Archie, but nobody else dared to lay a finger on Will Sparrow’s little brother. As long as they kept to the rules, they got on very well. After the boys had eaten they were kicking a ball around under a tree when Jenn came running to meet them with her pinafore flapping about her.

“We’ve all got to go to the Hall!” she shouted. “Everybody on the estate, all the gardeners and keepers and everyone!”

“What for?” called Will.

“How would I know!” she said. “Ma says go home first, have a wash and put your Sunday boots on!”

Archie looked up at Will to see what he made of all this.

“Reckon somebody’s died,” said Will. “The Hall, and Sunday boots. Must be serious, whatever it is.”

The outside staff stood awkwardly in the Great Hall at Ashlings, the men and boys with their caps tucked into their belts. The indoor servants were there, too, the maids and valets and manservants, but they were used to the grandeur of Ashlings Hall, and wore uniforms. Archie tried not to stare, but he reckoned they could fit Gardener’s Cottage into the Great Hall alone. It reached up through two storeys, and had a galleried landing with doors opening from it and pillars holding up the ceiling. Opposite the front door was a wide red-carpeted staircase, the kind Cinderella might have run down with her shoe in her hand. There was a great stone hearth in one wall, but no fire in it on this warm August day. Opposite were the gleaming double doors of what somebody said was the drawing room.

Gardener’s Cottage looked as if it had grown from the earth, as if tree, root and stone had worked and woven themselves into a place where a family could live comfortably like badgers in a sett. No angle of the walls was completely true, no line was perfectly straight. But the Great Hall at Ashlings was all straight lines, as far as Archie could tell. Plenty of space but too much of everything, too much polish and paint, too much carving and all those pictures on the walls in frames too big for them – and not a fingermark on anything. Archie glanced down at his hands. After all that scrubbing there was no more ingrained dirt on his hands and even his nails were clean. He wished he knew what he’d cleaned up for.

The drawing room doors opened from the inside and Grant the butler appeared. He was grey-haired with a lined face and stooped a little, but he still looked ten feet tall in his shiny shoes. Behind his back Will and Archie called him Grunt and said he was so old he had to be dug out of his coffin every morning. Today he looked so grim that it was almost funny – and in another way, not funny at all.

“Lord and Lady Hazelgrove,” he announced. “And Mr Edward.” Will had been right, it must be serious. Nobody ever called Master Ted “Mr Edward”.

There was a soft gasp from the staff as the Hazelgroves stepped into the Great Hall. Usually, Lord Hazelgrove wore tweeds that smelt of wet dog and tobacco. Today he was in his army uniform, the buff-coloured tunic and dark trousers of an officer in King Edward’s Guards, with a row of medals over one pocket. His grey hair was neatly brushed. He had a lean face, and today looked so sad that Archie felt sorry for him.

Master Ted was in uniform, too, like a younger and slimmer version of his father. At the sight of them every man and boy in the room stood a little straighter and taller. Even beautiful Lady Hazelgrove, in a tight little buttoned-up jacket and plain skirt, looked soldierly. Connel was at her hip and the big shambling gun dogs, Brier and Sherlock, followed Lord Hazelgrove. Star pattered after Master Ted, sat down and, to Archie’s disgust, scratched.

“Ladies and gentlemen of Ashlings,” announced Lord Hazelgrove solemnly. “Thank you for joining us here at such short notice, and such great inconvenience. I would not lightly call you away from your work, but I have a serious announcement to make, and I wish you all to hear it together.”

I wish he’d hurry up, thought Archie. Just tell us who’s died.

“It is my sad duty to inform you,” said Lord Hazelgrove, “that this country is at war with Germany.”

This time it was not a soft gasp, but a sharp one. From some of the women, it was almost a shriek.

Lord Hazelgrove began to explain why they were at war but Archie, though he tried to follow, was soon confused. He understood that somebody very important had been shot in a faraway land and as a result there had been arguments between countries he’d never even heard of. But then the German king, the Kaiser, had sent his armies to take over the small country of Belgium.

“Britain has a duty to stand by Belgium,” said Lord Hazelgrove, “and therefore we are at war with Germany. This will make a difference to all our lives.”

Archie turned to exchange glances with Will, but Will wasn’t looking at him. He stood straight as a birch tree with his head high and his eyes fixed on Lord Hazelgrove. He looked ready to march away.

“Before long,” continued Lord Hazelgrove, “the army will be looking for men to go out and fight. There will be a recruiting office in the village, and men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-eight may apply. Before you all start queuing up, there are things you need to know. Lady Hazelgrove and I are proud to say that we have always taken care of you. Any of you under or over age, don’t even consider going to the recruiting sergeant and lying about it. I will personally drag you back by your collars. And men with families, you can hold back.”

Dad wouldn’t be going, then. That was a relief.

“Some of us were around for the last business in Africa,” went on Lord Hazelgrove. “War is never a good thing, but it is sometimes a necessary one. If any of you do want to join the army, your job will still be here for you when you come marching home. Your wages will be set aside for you. But I also want to say to you, if you want to join up, come and talk to me first. I’m not just your employer, I’m an old soldier too.”

The back of Archie’s neck itched, but he didn’t da

re scratch it. Lord Hazelgrove still hadn’t finished.

“My son Ted will return to his regiment this week and his brother Simon is already preparing His Majesty’s Navy. As for me, I’m off next week to an army training camp. They need old crocks like me to knock the recruits into shape.”

Archie tried to concentrate, but the itch at the back of his neck was so bad that he was curling his toes in his boots. He thought his eyes would water or cross.

“I will be here all day for anyone who wishes to speak to me,” went on Lord Hazelgrove. “Just come straight here and ask. It’s that simple. Now, I’m sure you’d like some refreshment so tea, lemonade and biscuits are to be served. Ladies and gentlemen of Ashlings, three cheers for His Majesty the King!”

When the cheers had been shouted Archie finally took a good scratch at the back of his neck. A long trestle table covered with a white cloth stood beside the empty fireplace, and unsmiling housemaids bustled about with jugs of lemonade and enormous brown teapots. Some of the male staff were already lining up to talk to Lord Hazelgrove while others stood about, young footmen in suits with their hair slicked down, talking, watching each other’s faces as if they were playing a guessing game. Are you going to war? What do you think? Are you?

“As far as I can see,” said a short and muscular housemaid with a teapot, “it’s nowt to do with us. It’s all Germany this and Serbia that. Let them sort it out.”

“We have to stand up for little Belgium,” said Mr Grant. “If the Kaiser isn’t stopped he could be in Britain this time next year, we’d have Germans running the country. Is that what you want?”

“No, Mr Grant,” said the housemaid meekly, but she pulled a face behind his back as he turned away. “You two Sparrow boys, do you want lemonade?”

Archie and Will took their glasses of lemonade and sat outside in the sunshine, on the front doorstep. Ashlings had always looked so solid with all that land, the Hall and the cottages. It seemed impossible that any of it should ever change. What if Mr Grant was right, and German soldiers would take over?

Archie's War

Archie's War